If you happened to be in my neck of the woods this past Monday, you might have noticed throngs of young people gallivanting about on the streets. With the men in dark suits, and the women dressed in elaborate long-sleeved (furisode) kimono and faux-fur wraps, it might seem like they were on their way to a high-school dance (though they don’t have those here) or something similar.

That’s certainly what I thought when I first encountered these groups back when I studied abroad here. But actually, the 15th of January marks Adults’ Day in Japan, and, thanks to the government’s “Happy Monday System” for national holidays, it was observed just this week. The age of majority here is 20, and all 20-year-old men and women dress to the nines, then converge on a predetermined location to listen to boring speeches by politicians about the meaning of responsibility and adulthood. That rite solemnly passed, they are then set loose upon the town, most choosing to exercise their newfound alcohol-purchasing power. The news the next morning is usually full of reports about disorderly youths. So much for that “responsibility”.

As for me, I’m getting back into the swing of classes this week, but while my travels are still fresh in my memory (mostly from every single teacher asking me if I went back to the US), I should try and relate them to you, as well. So that brings me to my first destination on my five-day odyssey: Amanohashidate.

Located on the Tango Peninsula in northern Kyoto Prefecture (in layman’s terms, about four hours north of Osaka, with good connections), Amanohashidate (roughly, “Bridge of Heaven”) is a famed… sand bar. It spans Miyazu Bay with a distance of 3.2 km (about 2 miles), and is covered by about 7000 pine trees. In spite of this rather humble description, it is known throughout Japan as one of the country’s “Three Great Views”, as set forth in the 17th century by a Confucian scholar connected to the Tokugawa Shogun. Its image was then made famous in a woodblock print by Hiroshige, a master of the art, around 1860. So, sandbar though it may be, its reputation precedes it. And besides, I’d already got to see one of the other two Great Views—Itsukushima Shrine in Hiroshima—back in 2006, so I figured it’d at least get me one step closer to completing the hat trick.

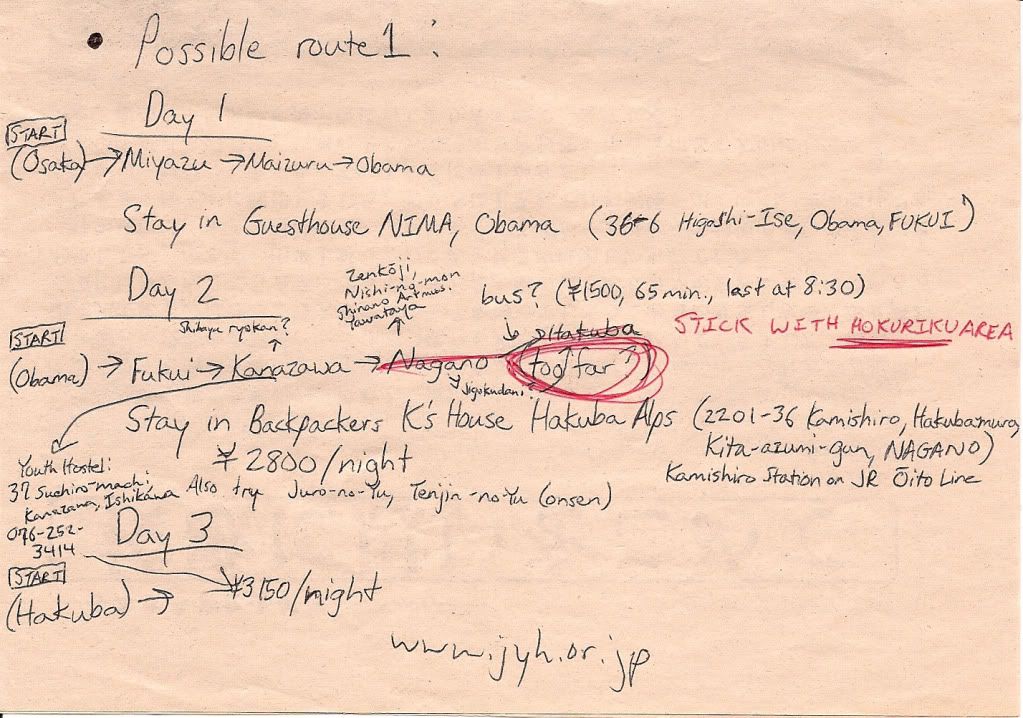

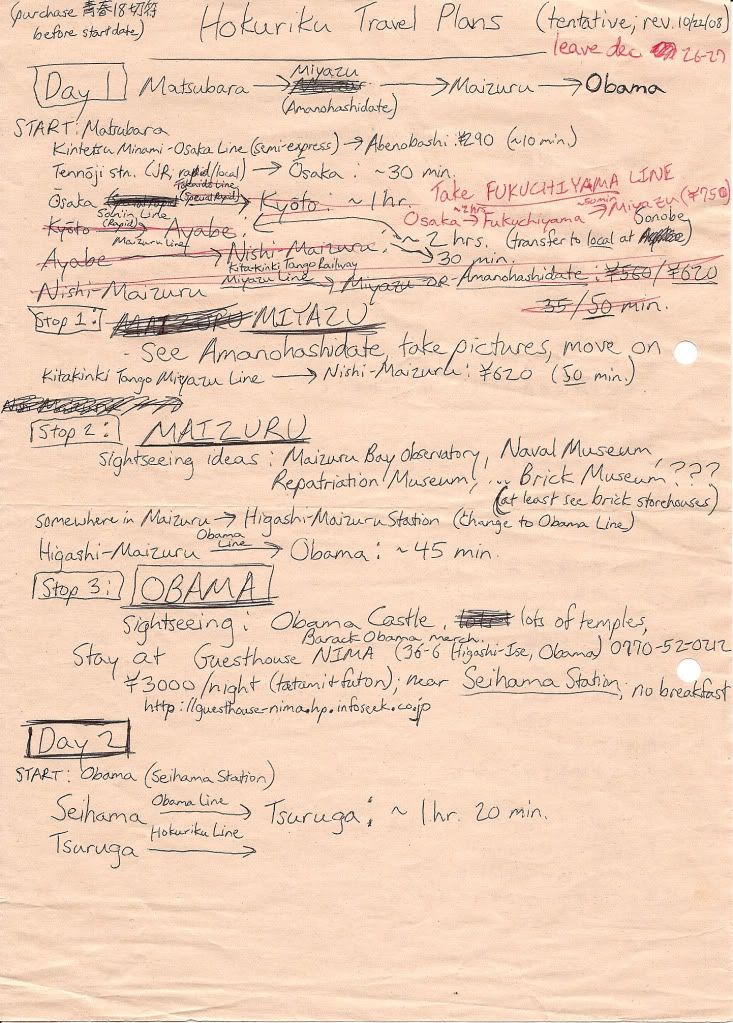

I’d only just decided the day before that I would be better off doing the journey as a day trip: scrutinizing my map and the train timetables, I realized that I’d be hopelessly late for supper at my first port of call if I followed my itinerary to the letter. (This, you must understand, was after I had pared it down from reaching Nagano in three days, which I might have been able to do in real life if I never actually got off the trains.) So, splitting my first day into two and plotting out a more leisurely first outing, I had my revised plan all set… only to wake up at 6:45, or just about the same time my train was supposed to leave. Throwing on my clothes and grabbing my camera, I took off for the train station, but the damage was already done: when you only have one train per hour where you’re going, the slightest delay means a fairly long time spent, well, killing time.

And it was cold. I’d forgotten that the center of Japan, in between the coasts, is also quite mountainous; the elevation at my first transfer station, combined with a genuine cold snap that day, left me shivering even with multiple layers on. So I bided my time, first at Sasayama, and later at Fukuchiyama, taking pictures of trains I couldn’t board and generally trying to stave off frostbite and hypothermia. Nevertheless, the snow up north was a sight for sore eyes, and even though I was no longer entirely sure whether I had earlobes, it was enough to put me into a state of blissful serenity for the rest of the day. Or at least until my toes started to complain as well.

Arriving in Miyazu just past noon, I surveyed my options for taking in the scenery. The aforementioned woodblock print depicts Amanohashidate from the southeast, in what’s known (perhaps a bit over-ambitiously) as the “Flying Dragon View”. I thought about doing likewise, but on closer inspection, the observation point was now part of “Amanohashidate View Land”: essentially a tacky, glorified children’s playground overlooking one of Japan’s most majestic sights. Thanks, but no thanks. Instead, I chose to take a ferry across the bay to Kasamatsu Park, which houses something equally famous: the renowned Mata-nozoki-dai (“between-the-legs viewing platform”). That’s right: the accepted method of viewing Amanohashidate, as passed down through the generations, is to bend over and gaze at it upside-down. Apparently, it’s supposed to make it look like it’s floating in the heavens. Or maybe the locals were just having a laugh at the expense of travelers who’d come from all across the country to see their sandbar. Either way, I set my mind on coming here.

Taking the ferry across, I stood against the railing under the falling sleet, watching the fog roll across the mountains while sea gulls darted, dove, and glided around the boat (the ferry operators were actually selling snacks for the wannabe-pigeons on-board, which I declined). The rest of the passengers were Chinese-speakers who didn’t seem to like the cold much, so I had the outer deck to myself. Immersed in the open air, I reveled in the feeling of being out on the water with the wind on my face, which I hadn’t experienced since I’d left the U.S.

One short hike and cable-car trip later, I finally found myself looking out across the bay, onto Amanohashidate itself. I was a bit surprised to learn that the mass of trees we’d passed on our way to the opposite shore was what I’d come to see, but from above, it was breathtaking. Almost on cue, the sleet eased up, the clouds rolled back, and I could see across the bay, out onto the sea in one direction and up into the mountains in the other. It really was worth the trip, after all. Feeling particularly pleased with myself, I decided to give the upside-down viewing a shot. Maybe it was just the dizziness from all the blood rushing to my head, but from that angle, it really did look as though it were a bridge floating in a particularly choppy sky. I dutifully took several more photos from both orientations, and then headed back the way I’d come. After all, it would take just as long to get home as it did to get there.

Of course, being me, it’s not like I could sit back and enjoy my evening once I got back to Osaka. Planning out last minute travel arrangements, stuffing an assortment of items into an already hopelessly overloaded backpack, and looking around frantically for one more pair of wool socks, I finally sank into a fitful sleep around one in the morning. With an intended departure time of six o’clock, this wasn’t going to turn out quite as I had planned….

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: My entire album of photos from the day is available for your perusal online. Check it out. At the moment, I can’t get the slideshow feature to not go backwards starting from the last image taken, but I’ll work that out later. For the time being, just navigate through by clicking the left-arrow button that appears when you mouse over the image. Or click “View All” and see them at your leisure.